Категории:

ДомЗдоровьеЗоологияИнформатикаИскусствоИскусствоКомпьютерыКулинарияМаркетингМатематикаМедицинаМенеджментОбразованиеПедагогикаПитомцыПрограммированиеПроизводствоПромышленностьПсихологияРазноеРелигияСоциологияСпортСтатистикаТранспортФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияХоббиЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Regularity and variation in language

Two views of context

Practically every discussion about the role of context in the determination of meaning starts with the vexata quaestio of its extension: what exactly should context include? How can we fix its limits? There is no agreement at all on what we should take as being context; the notion ranges from the entire encyclopedia understood as the historical and cultural horizon within which each text is collocated, to the extralinguisric "surroundings" that constitute the communicative situation of a given utterance, Го the strictly restricted linguistic context, which is sometimes termed co-text. This range reflects the perspectives of the disciplines which have cause to resort to context: the restrictive reading of context as Unguis tic surround or co-text is characteristic of textual grammatical studies,1 while anthropology, ethnology, and sociolinguistics tend to extend the area of application to the more general socio-cultural aspects underlying communication.2

The different notions of context reflect different methodological perspectives which, as Bertuccelli Papi (1993: 186) has observed, depend both on the objectives of the analysis and on the object of study. From the point of view of the determination of lexical meanings, the question of how far context extends can he posed in a way that is in some way at odds and partially independent of its definition: the real problem is how to view the relation between lexical meaning and contextual components, both intra- and extratextual. This relation is often seen as a series of transformations effected by context on a hypothetical pre-existent and non-contextual meaning. Posed in this way, the problem presupposes an implicit opposition between meaning in context and meaning outside of context; however, we shall see that talk of non-contextual meaning is misleading because meanings "outside of context" do not exist in reality.

The equivocation derives from the widespread and unquestioned acceptance of what I would define as an externalist view of context—how much and in what way a certain "surround" modifies the meaning of a word. I would like to attempt to shift the perspective, to turn it inside out and give it an internal focus. We can ask not so much what (he context does to the word but above all what the word does to the context, what sense-producing potential the word has in relation to its "surround." I will call this an internalist perspective.

А С

(Buyer) (Seller)

D

(money)

Diagram 16

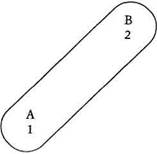

phenomena such as relations of synonymy and semantic opposition. Fillmore develops this point by examining the relations between terms belonging to the same scene, for example, the converse terms sell and buy, which display a superimposi-tion of meaning. I would like to suggest that the analysis can also be extended to terms that do not belong to the same scene. Let's take as an example the case of get. Unlike buy, its representation does not involve any concept of exchange, just the transfer of something. Get can be represented by the schema in diagram 17, which has just three roles. In English, however, the two verbs are fully interchangeable in certain contexts:

8a. Did you get the newspaper today? 8b. Did you buy the newspaper today?

9a. I forgot to get the bread. 9b. I forgot to buy the bread.

In order to explain the systematic nature of these substitutions it is not enough to say that the context determines the selection of certain features; in fact, it is the regularity of the selection process that is interesting in these cases. What ensures that in these contexts get is systematically interpreted as a synonym of buy? It seems to me that the regularity of the substitution can easily be explained by referring to the underlying schematic structure: get is interpreted here against the background of the scene of the commercial sales event that underlies buy and thus activates that part of the frame present in buy but not in get, that is, the component of "exchange" instead of the pure "transfer." The activation of this frame modifies the meaning of get and allows a synonymous substitution.

The articulation of a deep conceptual level displays the experiential (and in this sense also realistic) characteristic of semantic representations of this kind: words are understood only if they are projected on the complex background of our experience of the world, which means that the semantics of language is inseparable from a "semantics" of the world and our experience of it. This reveals the intrinsically encyclopedic nature of the model, which involves much more than the quantity of information included. From a purely quantitative point of view, the schema of the commercial exchange proposed by Fillmore may appear rather "flimsy," because it includes only those roles essential to the definition of the concept, leaving out, for example, typical elements that are more closely connected to the cultural connotations. The encyclopedic nature of the model can also be seen in its format, which is semiotically "mixed" and not reducible just to linguistic properties; the frequent and characteristic use of figures, diagrams, and iconic representations within frame semantics and many other models developed in the field of cognitivism is significant from this point of view.

I----------------;---------------------------------- set --------------------------------------------------1

с

(source)

I )iagnun 17

Default values and typicality

If we look more closely at the examples considered thus far, we can see that although in each case the term activates a frame, the properties activated are not of the same kind. It is here that the distinction between typical and essential properties proves so productive. There are restaurants without menus or without waiters serving at the tables, but a restaurant where you could never eat would not be a restaurant. In other words, the slots of a frame, to adopt the terminology of artificial intelligence, relate to values that have different roles in the representation of a given term; some are typical values while others are essential to the definition of the meaning. We saw in the last chapter that both essential and typical properties can be included in frames, as in prototypes. Now, although each term activates all the properties of its frame or typical occurrence, not all of them can be

considered default values: only typical components are default values of the representation.

We must remember that in the representation formulated by artificial intelligence, default values are those values assumed to be valid in the absence of explicit indications to the contrary, indications which can, however, always be introduced without thereby altering the meaning. What this means is that the fundamental characteristic of default values is their erasability. The typical restaurant has menus, waiters, and tablecloths, but each of these elements is a property that can be erased, leaving simply an atypical restaurant. Green lemons, albino tigers, and white whales are all non-typical exemplars of their respective categories, but they are still respectively lemons, tigers, and whales. Typical color is a default value. In the absence of information to the contrary, we assume that lemons are yellow, tigers have stripes, and whales are dark-colored, but these properties can always be erased in that they are typical but non-essential. On the other hand, the facts that lemons are fruits, tigers are feline, and whales are mammals are not default values but properties that cannot be erased without renegotiating the meaning of the terms. Something similar occurs in complex scenes activated by ptedicates: pran-zare necessarily implies that something edible is consumed. This feature cannot be erased and is not assumed by default.

The difference between the two types of property clearly emerges if we use the test of the adversative but, as we saw in chapter 6. But can block typical properties, the subject of probable inferences, but not essential ones, without producing a semantic anomaly requiring subsequent explanation or textual elaboration:

6. It is a tiger but it is albino.

(I.e., it does not have stripes which, by default value, we would typically expect it to have).

7. It is a lemon but it is green.

(I.e., it is not yellow as, by default value, we would typically expect).

8. * It is a tiger but it is not an animal.

9. * I had lunch but I did not eat.

Although typical values are not homogenous and it is possible to distinguish between different forms of typicality according to the various lexical categories,12 they are all characterized by their erasability—typical properties are the set of default values of a frame or prototypical scene. Differentiating between typical properties and essential properties is thetefore important from the point of view of comprehension, in that we can then specify the components of a semantic frame that are operating as default values, that is, as a probable but not certain inferential base.

Pathemic semes

We now need to ask to what extent this level of meaning comes into a description of the linguistic meaning of individual tetms. Is lugubriousness a semantic property of black? I believe that this problem, and similat ones in linguistic semantics, must be resolved on a linguistic basis. The deciding criterion should be, in my view, the following: whete conventionalized extensions of a certain property are tegistered in the semantic system of a given language,' this property should be part of the meaning of the term in question. In fact, we have a great many metaplmri cal and dysphoric extensions of black. Considet expressions like:

My future looks black. I am in a black mood. Black humor

in which the meaning of the adjective is not a chromatic quality, but an emotive tonality. None of these expressions could be understood if ibis tonality were not registered in the semantics of the term and did not constitute an integral pari ol competence. Once again, llie lesl for verifying the adequacy ol ibe semantic rep resentaiion is comprehension anil the practical process ol interpretation.

The phoric component of value can be directly inscribed in the lexical meaning of many terms, as in the pairs slim/skinny, or thrifty/stingy. Their semantic difference can only be explained by drawing on an axiological component based on the euphoric/dysphoric opposition. It is important to stress the inadequacy in these cases of a classic connotative model which would account for these phenomena in terms of additional connotations superimposed onto the basic meaning. Valorization is here a primary element of semantic organization, not a secondary meaning that could be erased, and is conveyed by specific semes that we could call pathemic semes.

In other cases, lexical units include in their meaning a pathemic component whose euphoric or dysphoric axiology derives from an element that could be called enunciative perspectivization. Think of the difference between noun phrases like a violent bbw and a painful blow. An implicit point of view is inscribed in each expression regarding the subject of the enunciation: in the first case the blow is oriented according to the perspective of the person who inflicts it, in the second to that of the person who receives it. Pathemic aspects of this kind can often be found at a lexical level, above all in qualifying adjectives; frightening, terrifying, and terrible, to give just a few examples, qualify an event or entity, but at the same time presuppose a subject who experiences the feeling of fear or terror, thus constructing an implicit relation of subject and object. If something is terrifying or frightening, it must necessarily be so in relation to an implicit subject who feels that emotion and who is textually inscribed by that lexical choice.

io.$.$. The heterogeneity of semes and the stratification of content

The analysis carried out thus far regarding the different nature of the properties comprising the semantic universe of a language reveals an intrinsic heterogeneity of constitutive semes, which not only include different qualities, but seem also to refer to different levels of pertinence and depth. To put it in more Hjelmslevian terms, the substance of content is stratified according to a hierarchy of levels,

whose extreme levels (which are also the most important and noted ones) are the physical level on the one hand and the level of apperception and evaluation or collective appreciation on the other. (Hjelmslev [1957] 1959)

The most interesting aspect of the stratification of content is the priority of the axiological or evaluative level, which is stressed by Hjelmslev on numerous occasions.

Clearly, it is evaluative description that imposes itself before all else in the substance of the content. It is not through a physical description of signified things that one can usefully characterize the semantic use adopted by a linguistic community and belonging to the language that one wants to describe; on the contrary, this can be obtained through the evaluations adopted by this community.

the collective appreciations, social opinion. (Hjelmslev [1954] 1959) It is the level of collective appreciation which constitutes the constant presupposed (selected) by the other levels, including the physical level (which, as we know, may be absent), and which by itself enables (amongst other things) a scientifically valid account of "metaphor." (Hjelmslev [1957] 1959)

Metaphors in effect constitute an important area for verifying the priority and immediacy of the evaluative level which, as I argued earlier, is directly pertinent from a linguistic point of view, and the only one, according to Hjelmslev, which is simultaneously important on both the linguistic and the anthropological planes. The priority of value is also sustained by Greimas, albeit not on the anthropological and social plane that Hjelmslev focuses on. According to Greimas, the thymic may be thought of as a precondition of meaning, and its priority is onto-logical, in relation to the very possibility of meaning. It constitutes the deepest level of semanticism, affecting the fundamental, elementary structures of signification with its euphoric and dysphoric values. This position is very similar to that of Gestalt psychologists who claimed that tertiary properties have priority over all others. (According to Wertheimer, black is lugubrious prior even to being black.) At the very foundation of meaning, at its deepest level, prior perhaps to any convention and code, we find a pulsional intentionality made up of emotions and sensations rooted in our corporeal, perceptual, and psychic organization and in the valencies which, perhaps already inscribed in the forms of the natural world, color our world with values, affects, attraction, and repulsion.

10.6 Semantic structure and linguistic classes

As yet largely unexplored is the relation between the articulation of the semantic system and its possible differentiated distribution in the various parts of speech. Is thete a regularity between items of expressable content and a tendency for them to be codified in certain linguistic classes rathet than others? In other words, do linguistic classes have a semantic basis? And to what extent can models which ate valid, for example, for nominal semantics, be extended to other parts of speech? As far as the first of these questions is concerned, the general tendency in linguistics and cognitive semantics is certainly oriented toward the search for a semantic motivation for linguistic categories; a number of important contributions have already been made to this end, especially in terms of the different distribution of content between open classes and closed classes. The important work of Talmy (1983, 1988a) has clearly shown that there are precise limits on the type of semantic information conveyed respectively by the lexicon and by grammar. In Talmy's terms, information conveyed by the lexicon consists of semantic elements codified in open classes (roots of nouns, verbs, and adjectives), while grammaticali/.ed content is expressed by closed classes (prepositions, pronouns, articles, particles, and all inflectional morphemes). These two components of the

linguistic system carry out radically different functions: while closed classes supply the fundamental structure of the language, its structural skeleton, open classes convey elements that are more properly content. This involves a precise qualitative distribution of the information codified in language, because only some items of content can be grammaticalized, while others never are. In particular, the grammaticalized content expressed in the closed classes is topological and non-Euclidean, while content relating to the phenomenological aspect of entities (colors, form, size, and absolute dimensions, that is, figurative semes in Greimas' terminology) is never conveyed by closed-class elements. Closed-class elements relating to spatial determination (prepositions, deictics such as this, that, here, there, etc.) are neutral in relation to the form, physical appearance, size, and modality of movement of the entities they apply to, and express abstract schematic relations which are topological and relative, never absolute.20 The specific perceptual qualities of an object (we could say its exteroceptive semes)—form, size, and general figurative configuration—are, on the other hand, expressed by open-class elements such as nouns and adjectives. For instance, absolute distances are expressed by various systems of numerals, colors by adjectives, and forms by the open class of nouns. Thus, alongside the small number of closed-class terms, such as spatial prepositions, which refer to a relatively few abstract schematic structures of a topological nature, we have a very large number of nouns for specifying the innumerable forms of objects.21

It is interesting to observe that these different fields of specialization of the lexical and grammatical components of the language configure an opposition between perceptual-sensory properties (such as form, size, color, absolute distance, etc.) and structural properties connected to topological schemes that are not based on the sensible properties of the object, but rather on schemata of deep images which may be linked to corporeal structuring.

The search for a semantic basis for linguistic categories undoubtedly characterizes the whole cognitive approach to the study of meaning, and also extends to the characterization of the different semantic configurations underlying classes that are formally definable as verbs, nouns, and adjectives. The work of Langacker (1987), Haiman (1985), and Wierzbicka (1985) all moves in this direction; none of them reduce the syntactic to the semantic, but rather all are concerned with the identification of a more adequate principle of semantic motivation which can account for the close connection between form and meaning. To argue that linguistic categories have a motivated basis is to claim that they have an ontological foundation which in each case refers to an experiential base, even though this is not necessarily identifiable at the same level. According to Givon (1979, 1984), for example, the main grammatical classes reflect a scale of temporal stability of denoted phenomena: at one end of the scale we find experiences which are relatively stable in time, linguistically codified as nouns, and at the other end there are experiences of rapid change, that is, events and actions, typically codified as verbs, a linguistic class whose existence is closely dependent on time. Between the two

extremes there are experiences of intermediate stability, linguistically represented in the class of adjectives. Givon (1979) also observes that although there are both concrete and abstract nouns, the latter are always derived, generally from verbs. This would seem to suggest that the basic semantic configuration for the nominal class is that which codifies physically determined and spatially delimited entities. In this way, the difference between semantic categories like abstract and concrete derives from distinct ontological bases (a perspective similar to the one I have delineated). Thus it is possible to motivate the different formats of the various lexical classes by starting from the different experiential saliencies underlying them.

The hypothesis of Brandt (1995) is similar; in his view, nominal, verbal, and adjectival classes stabilize different semantic worlds, respectively those of perception, communication, and imagination, which roughly correspond to the fields of physical experience, social experience, and psychological experience. There would thus be a physio-semantics, source of the sub-language of states, expressed by nouns; a socio-semantics, source of the sub-language of events, expressed by verbs; and finally, a psycho-semantics expressed by adjectives and adverbs. Naturally this tripartite division must be taken as a working proposal, but it may constitute a starting point for a more detailed analysis of the semantic-ontological bases of linguistic categories, an area which is as yet largely unexplored.

The more specific problem of the possible extension of the prototype model can be framed in this context. Can the notion of typicality, which has proved useful for the categorial structure of concrete nouns, also be applied to other parts of speech such as verbs and adjectives? The issue is controversial. Some argue that prototype semantics is essentially a nominal semantics; however, studies like Coleman and Kay 1981, Jackendoff 1985, and Fillmore and Atkins 1992 suggest the possibility of extending prototypic analysis to predicates. Pulman (1983) also recognizes a difference in the degree of typicality of actions expressed by verbs, ' and this is confirmed in more recent works on other semantic fields, such as verbs ol perception, which reveal phenomena of differentiated saliency.24 According to Kleiber (1990: 129), however, the intuitive pertinence of a hierarchical structure within nominal and verbal classes is not the same. In his view, one of the dilficul ties of extending the prototype model to non-nominal classes is that often reference is being made to the situation which the predicate denotes rather than CO the prototype of a category. An example of this is the case of adjectives of scale like big, small, good, bad, and so on. Clearly, we cannot talk about a single prototypical meaning for bigot goodifwe do not specify the category of referent to which the adjective is applied each time. A big ant and a big mountain do not have the same prototypical dimensions.

In general, one can agree with Kleiber that there is an intuitive difference in the meaning of" prototypical case when applied to classes such as natural kinds and when applied to adjectives of scale or verbs and the complex scenes that these relate to. I hinted at this problem in chapter 8 when introducing the concepts of

frame and scene used by Fillmore. Scenes represent complex situations that describe the context of regularity of a certain action, rather than the central exemplar of a category.

The idea of a typical scene allows us to grasp a fundamental characteristic of linguistic functioning linked to the effect of distortion that I have already discussed: the relation between our experience of reality and the words with which we speak about it is neither a biunique correspondence nor a precise mirroring. This distorting gap, which cannot constitutively be eliminated, gives rise to a series of procedures of local "readjustment"; processes of analogical extension are one of the most important examples of this, in that they allow the application of a description which is valid for the typical or regular situation to anomalous or deviant situations. Let's consider the meaning of a verb like run. It has been said that the prototypical situation for run is a running man rather than a running crab. Certainly, one could easily object, as Kleiber does, that it is improbable that the categorization of a token of run is made each time on the basis of a comparison with the prototype of a running man. But the assertion can be reformulated: if "a human being runs" can be considered the typical case of run, it is because this phrase refers to a situation for which we have direct and phenomenologically founded knowledge. Verbs of movement come into the class that I have called natural actions because of an affinity with natural kinds, the linguistic description of which is impossible without referring to the underlying physical-perceptual experience. Run does not only mean "move rapidly" but refers to a particular form of corporeal movement that is understandable only in relation to our upright position and to our having two legs.25

It is, therefore, on the basis of our corporeal experience, the structure of our body, and its vertical position that we know what run means for a human being; starting with this primary meaning we broaden the use of the same expression to describe the movement of a crab or a millipede. A crab or a millipede certainly does not run like a human; this is one of those cases which are continually found in linguistic use where the applicability of a word is extended beyond its typical conditions. In these cases, the distortion of the linguistic description is, so to speak, adjusted, following analogous reasoning procedures: if a crab runs, we imagine that it is moving in a way which has similar features to the way a human runs, even though we know that this similarity is only partial and limited, given the structural difference between the body of a crab and our own.

I believe that many of the equivocations present in discussions like this one would be clarified if, instead of arguing in essentialist terms about the prototype as the best exemplar of the category, the inferential perspective I have indicated were to be adopted. In this perspective, the typical case becomes the hook, and point of departure, for possible inferences, an abductive tool onto which can be grafted an interpretative procedure.

Even if we come up with a new word to indicate the way a crab runs, just as we have trot and gallop for a horse, it would be hard to denominate uniquely the way each animal species rims. Our mnemonic resources would impede i(. Pioce-

The Many Dimensions of Meaning

dures of analogical extension are not a choice but a fundamental necessity in order to live with the distortion implicit in linguistic functioning. Thus the intrinsic limitation of language is made up for by its almost limitless flexibility. The number of words at our disposition will always be limited and woefully inadequate to describe the multiplicity of the real: the world contains more things than we will ever be able to name, and our experience is constantly confronted with the limits of our words. But at the same time our language always seems able to transgress its own limits, and also our own.

NOTES

Three Approaches to Meaning

1. Just think of the concept of representamen in Peirce, which is already a sign and not a pure signifier.

2. Referential semantics is a deliberately generic term referring to all those theories which are based in some way on notions of reference and truth.

3. There are innumerable works in English, beginning with the anthology edited by Rorty (1967).

4. There are certain differences on this point within the analytic camp; one cannot talk of an anti-psychological approach in the case of philosophers like Quine or Grice. However, in general terms, one can say that cognitive aspects of meaning are not the central concern of the analytic philosophers.

5. This is the principle of compositionality formulated by Frege ([1892a] 1952), according to which the meaning of complex expressions is determined by the meaning of the simpler ones within them. On the basis of this principle, it can be established that the meaning of an expression depends on its contribution to the meaning of the sentence which it is part of.

6. The concept of model is used here in a quite different way to the meaning it usually has in a scientific context. Model-theoretic semantics sets out to assign to each expression in language a given interpretation which can be seen as a model of that expression. No version of model-theoretic semantics effectively interprets a language in relation to the world; at most it illustrates a kind of model, making use of set theory and showing how it is possible to systematically correlate expressions and sets of objects (elements and sets). The function of correlation (interpretation) and the domain of base objects are called "models." For example, if a noun is correlated to an element and a predicate is correlated to a set of elements, the sentence which is formed by correlating the noun and the predicate will be considered true if and only if the element correlated to the noun belongs to the set correlated to the predicate.

7. VS. Kaplan 1977.

8. Kripke never actually explains this point hilly, but the most widely accepted interpretation ol his position points in this direction,

9. In the history ol semiolic thought the idea was certainly not a new one. ( loiisider, in particular, the Stoic model if. Males 195).

Notes to Pages 10-15

10. In these cases the overall truth value of a statement like John believes that Mary loves him does not depend on the truth or falsity of the completive Mary loves him, which is an opaque context. John may believe to be true what is in reality false, but as die statement regards the beliefs of John, it is only the truth of these that determines the truth conditions of the sentence. In other words, the truth value of statements which occur in an opaque context does not contribute to determining the truth value of the sentence of which they are part.

11. The term possible world comes from Leibniz.

12. See, among others, the works of Barbara Partee (1979, 1982, 1989), Emmon Bach (1989), Lauri Karttunen, and Stanley Peters.

13. According to Chomsky, not all syntactic differences involve a semantic difference, while Montague believes that all syntactic differences have a corresponding semantic difference.

14. Other model theories do not use the concept of possible worlds. Of these, it is worth noting the situational semantics of Barwise and Perry (1983); they use the notion of situation, which corresponds approximately to a limited portion of the actual world. The main difference lies in the inherently partial nature of situations compared to the completeness of possible worlds.

15. For a discussion of this point, see, for example, Partee 1982.

16. It has been observed that the definition of intensional isomorphism is too powerful, given that any difference in the form of expressions makes synonymy impossible. The mother of my mother and my grandmother could not be considered synonymous because their inrernal structure is different. Carnap resolved this problem by considering some syntactic differences inessential. In order to be able to distinguish between inessential and essential differences, it is necessary to reduce linguistic expressions to their normal form, a kind of underlying form which reveals the structural identity even of expressions which have a superficially different form. This approach is very similar to the one adopted in generative grammar, where identical deep structures are assigned to expressions which have superficially different surface forms. From this point of view, one could regard the level of deep structure in generative terms as the level at which intensional isomorphism corresponds to synonymy.

17. Generative semantics was based on a program theoretically very close to the idea of intensional isomorphism, that of providing a representation such that identity and difference in linguistic form could predict identity and difference in meaning.

18. Montague argued that propositions are sets of possible worlds, properties are sets of individuals which possess that property, and individuals are the set of all the sets which have that individual among their members.

19. For a discussion of this point, see Bonomi 1987 and Marconi 1981.

20. Bonomi, for example, is extremely critical about this issue and, paraphrasing an observation by Lewis according to which a semantics without truth conditions is not semantics, states that "semantics without an adequate treatment of the lexicon is not semantics" (Bonomi 1987: 69; my translation).

21. For example, cf. Bach 1989.

22. Cf, for example, the Prague School, the theory of M. A. K. Halliday, linguistic argument theory (cf. Anscombre and Ducrot 1983), besides of course Grice's theory of implicature.

23. Note that here we are talking about resemblance and not identity; this introduces the idea of a gradual and graded dimension of resemblances and differences which is impossible in model-theoretic semantics, whose notions are caregorial and discrete. I will not immediately go into the need for shaded and non-categorial notions in the treatment of the semantics of natural languages, seeing that half of this book is devoted to a discussion of this problem.

Notes to Pages 16-24

24. The kind of truth which we refer to in natural language and its treatment in linguistics and semiotics will be discussed in section 1.4.3.

25. Course in General Linguistics ([1906-1911] 1983), henceforth referred to as CGL.

26. "The word has not only a meaning but also—above all—a value. And that is something quite different" (CGL: 114; my italics). "In a sign, what matters more than any idea or sound associated with it is what other sounds surround it" {CGL: 118, my italics). Here, although there is a claim for the priority of the differential aspect of value, a component of the signification relation, that is, reference to concepts, still seems to be present.

27. In particular, cf. Bally 1909 and 1932.

28. Cf. De Mauro 1965, Godel 1957.

29. Naturally, a similar problem also arises in terms of diachronic identity.

30. In particular, the oppositional component has an indispensable role in the representation of grammatical elements and closed sets such as prepositions or grammatical morphemes.

31. Associative relations were subsequently more commonly called paradigmatic relations. I will use the two terms without distinction.

32. According to Saussure, the site of associative relations lies in the brain, and such relations are part of the intetior store that constitutes language in each individual.

33. Saussure's example of the first kind of affinity is that between enseignement and armement or changement, because of the presence of the same suffix. An affinity of meaning is present in enseignement, education, and instruction, and a phonic affinity in enseignement and justement. It is interesting to note that recent studies of the mental lexicon find that all these critetia are drawn on; the associaive criteria also find confirmation in empirical data deriving from studies of errors and slips, which may be based on mix-ups due to morphological, semantic, or phonological affinities. On slips as interference between two simultaneously present words, see also Meringer and Mayer 1895.

34. On this point, cf. Eco 1984: 114.

35. For a detailed description, cf. Lyons 1977 and Cruse 1986.

36. In logical terms, the relation of hyponymy is defined as inclusion in a class, even if this definition presents the same problematic aspects already noted for the distinction between extension and intension. A more neutral definition from this point of view could be that of unilateral implication.

37. This is also the idea that undetlies natural taxonomies of kind and specific difference, usually represented by tree diagtams and binary branching.

38. See the data on the vertical organization of categories detailed in section 4.2.

39. Cf., for example, Baldinger 1980 and Gauger 1972.

40. Cf. E. Clark 1992. She argues for the existence of a pragmatic principle of contrast and shows how this governs lexical usage. The choice of a term is normally interpreted, on the basis of pragmatic implicature, as being contrastively motivated. The structuralist assumption that different forms contrast different meanings is transposed here onto a pragmatic plane as an interprerative principle of speakers.

41. Cf. Greimas 1966.

42. Semantic oppositions seem to be acquired very precociously; indeed, the process is completed at around the age of three.

43. In the many distinctions proposed to classify semantic oppositions, it is generally customary to distinguish between gradable oppositions {hot/cold, big/large) which are also called antonymous relations, and non-gradable or complementary relations (such as true/false, alinc/dcad, and so on). There are also converse pairs which presuppose an asymmetrical relation such as father/son, husband/wife, before/after. For a detailed treatment, sec-Lyons 1977 and ('ruse 1986.

44. In fact, there !■• .1 iiuihci level beyond ib.и (ii physical miasuremiml namely visual perception and its relation to linguistic structure. The lad 1I1.11 the color spectrum

Notes to Pages 25-28

has a precisely definable physical structure still does not tell us whether our perception and categorization of that spectrum is determined by the linguistic structure we possess (the thesis of linguistic relativism) or whether there are perceptual constants independent of language, linked to the psychophysiological constitution of our visual apparatus (the thesis currently sustained by cognitive research, cf. Berlin and Kay 1969).

45. At the beginning of the thirteenth century this conceptual field was covered by three terms, wisheit, kunst, and list, while a century later the lexical field had been transformed into wisheit, kunst, and wizzen. All of these terms also exist in modern German {Weisheit, Kunst, List, Wissen), but their reciprocal relations are different in comparison to either thirteenth- or fourteenth-century German.

46. According to Lyons (1977), the reality which Trier speaks of would seem to correspond to the substance of Hjelmslevian content. It seems to me rather to correspond to the concept of matter, in that it is a pre-linguistic, still-unstructured continuum. What seems to be missing in Triers analysis is the articulation of the substance of content as a level of organization which linguistic form imposes on the unstructured continuum.

47. Besides the work of Trier, that of Porzig (1934) also deserves mention. He was the other great theorist of semantic fields, interested above all in the syntagmatic relations which form a kind of series of micro-fields (see, for example, the relation between bite and teeth, blond and hair, climb and mountain). These privileged relations were to be treated in generative linguistics as selective restrictions linked to the representation of each single term. For each single lexical entry there is a specification of the possibilities of combination with other lexemes. Porzig attempted to treat these relations generally, even though these semantics restrictions are naturally extremely varied and heterogeneous: alongside very general terms like do or good there are many highly specific ones like fry or rancid. Porzigs approach was to treat these phenomena as progressive generalizations in linguistic use. All terms thus have an initial concrete and specific meaning which is then applied to wider contexts through successive extensions. Extension is based on processes of generalization and abstraction, that is, basic mechanisms of metaphoric extension. Leaving to one side possible judgements of this approach, it is interesting to note how it questions the assumption of the arbitrariness of the sign, given that in this perspective metaphoric extension is motivated by a general principle of extension from the concrete to the abstract. This is a very similar position to the one advanced by Lakoff and Johnson 1980.

48. Cf, in particular, Fillmore 1985 and Fillmore and Atkins 1992.

49. The characteristics of the contrastive aspect of frames and their similarities and differences with semantic fields will be examined more closely in section 8.3.2.

50. There are a great variety of positions: alongside radically critical views like that of Lakoff (1987), there are also those who, like Jackendoff, explicitly acknowledge a continuity with the Chomskian generative tradition.

51. Certainly, as far as semantics is concerned, this assumption has not had much of a follow-up because the study of meaning has never formed a central part of Chomskian research. Nevertheless, the cognitive assumption at the heart of cognitive semantics lies well within the Chomskian tradition.

52. This is the path taken by, among others, Fillmore, Lakoff, and Rosch. For a review of generative semantics, see Cinque 1979.

53. It is impossible to list everyone working in this field; some of the most well-known are Lakoff, Talmy, Fillmore, Jackendoff, Langacker, Fauconnier, Johnson-Laird, and Winograd, but this list is merely indicative and in no way comprehensive.

54. The following chapter is dedicated to a discussion of this point.

55. Naturally there are divergent positions regarding the specific treatment of each of these points.

56. In the eighties, there was considerable discussion about the compatibility of model-theoretic semantics and cognitive semantics. In 1982, Barbara Partce suggested two

Notes to Pages 30—35

possible responses: the separatist and the common goal positions. According to the separatist position, which is very similar to Fillmore's, the two versions of semantics have different aims, assumptions, and validity criteria. The common goal position, on the other hand, regards cognitive semantics and truth-functional semantics as parts of a common enterprise, even though, as Partee herself admits, it is not easy to see how this common ground is to be established. Within the composite panorama of cognitive semantics today, there are various different positions, ranging from the radical criticism of Lakoff (1988, 1987), Wilks (1988), and Winograd and Flores (1986) to much less extreme positions like those of Johnson-Laird (1983) and Fauconnier (1985). Both of the latter, for example, presuppose an intermediate cognitive and mental level between world states and linguistic expressions. This approach is compatible with the outcome of some recent work in formal semantics such as the theory of discourse representation (TDR) by Hans Kamp (1982). For a more detailed discussion, see Santambrogio and Violi (1988), and in general all the articles found in Eco, Santambrogio, and Violi (1988).

57. In particular, cf. Jackendoff 1983, 1987, 1991, 1992; Talmy 1983, 1988a; Langacker 1987, 1991.

58. I am thinking here above all of Fillmore and to some extent of Lakoff.

59. Cf. Eco 1976 and 1984. For a discussion of the concept of encyclopedia in the semiotics of Eco, cf. Violi 1992. The issue will in any case be discussed in chapter 7.

60. For a recent version of these positions, see Rastier 1987, 1991.

61. In particular, cf. Fillmore 1976a and 1976b.

62. Cf. also Clark and Chase 1972.

63. According to Marr, there are three distinct levels of representation of visual information, which range from the retinal apparatus to the final information codified in our spatial understanding. The first level (primal sketch) is responsible for the identification of the boundaries and edges of elements and their groupings. The second level (2V2 sketch), not yet three-dimensional but already possessing depth, organizes space into regions; finally, in the third level (3D model) the complete, three-dimensional representation of the object occurs.

64. At the level of corporeal representation, one can hypothesize that components like the opposition between tension/distension may be found; this is a central opposition for both the musical faculty and body movements, and is also very important for the level of the linguistic faculty most directly linked to the expression of emotions and affective states. The identification of the affective component in spoken language takes place above all at the level of intonation, a level traversed by phoric tensivity, that is, by the contrast between tension and distension and the relative phoric attributions. This is also a central problem in semiotic thinking (see the whole of Fonagy's work, in particular Fonagy 1983). Semiotics identifies tensivity and phoria as the two fundamental concepts constituting "the set of preconditions for the emergence of signification" (cf. Pezzini 1994: 154; my translation). Note that the semiotic approach, when talking about "preconditions of signification," also alludes to a not directly conceptual or conceptualized level, which is in fact the same as Jackendoff s hypothesis regarding the level of corporeal representation.

65. On this point, cf. above all Talmy 1983, 1988a, 1996; Jackendoff 1987, [992; Landau and Jackendoff 1993.

66. The objectivist ontology which underlies model-theoretic semantics is thus substituted by a constructivist approach: the world is not given as such but is the result ol a construction both at the level of perception and of conceptual categorization. This position does not preclude the existence of objective qualitative structures, which are not necessarily physical, in the perceived world. This is consistent with what is sustained in the ecological approach to perception ol "Gibson (1979) and in the model of Marr (1982). For a general discussion of these issues, which also covers the role ol abstractive categorization processes, cf. Lakoff 1987.

Notes to Pages 36-48

67. Discussion of this point always refers exclusively to the visual components of representation. Fot aspects of non-visual perception (tactile, gustatory, and olfactory perception), research is a long way behind and data are not yet available in any quantity.

68. This still linguistically determined, more surface aspect has been seen by some as a limitation of Fillmore's case theory (cf. Petitot 1985).

69. Here too it would be interesting to render explicit the references to the philosophic tradition, in particular the relation between image schemata and the notion of transcendental schematism in Kant.

70. Cf. also Sweetser 1990 and the catastrophe-theoretic semantics inspired by the theories of Rene Thom (Petitot 1985, 1992; Wildgen 1981, 1982).

71. Cf. Gruber 1976, Anderson 1971.

72. Cf. Violi 1991.

73. One cannot generalize in absolute terms; for example, this certainly cannot be said of the work of Fillmore.

74. For discussion and criticism on this point, cf. Violi 1996a.

75. For a discussion of the universalist and relativist issue in cognitive semantics, cf. Lakoff 1987, chapter 18.

76. Cf. Thom 1988; Petitot 1990, 1992; Brandt 1992, 1994, 1995, and Wildgen 1982.

77. On this point, cf. Geeraerts 1988a.

78. Cf. Chafe and Nichols 1986.

79. See, for example, the entry for "truth" in the Dictionary of Greimas and Courtes (1979): "It is worth emphasizing that the 'true' is situated within discourse, because it is made true by discourse itself, that is, it excludes any relation with (or validation from) an external referent" (my translation).

80. Obviously, cold indicates a property which is relative, and so the objectivity of It is cold is only apparent, because an enunciating subject is always presupposed. In other words, one could say that It is cold is a function with two variables, f(x,y), in the same way that I am cold is (I am indebted to Ivan Fonagy for this observation). There still remains the fact that the two formulations are very different from the point of view of the meaning conveyed. In terms of enunciation theory the difference is captured through the concept of enunciated enunciation.

81. On the basis of this assumption, it is possible to give an account of the continual semantic "adjustment" occurring in linguistic use: very often the terms which we use are not entirely appropriate, and in a model-theoretic semantic perspective this would modify the truth values of the utterance in which they appear. For example, if one held out a pencil and said Here's a pen!, the sentence would be logically false but "pragmatically" true as a response to a request for a pen.

82. From this point of view the concept of the cognitive dimension is situated at a different level from the intralinguistic dimension and the extralinguistic dimension: in principle, there are no theoretical reasons why the cognitive point of view cannot apply both to intra- and extralinguistic analysis. In practice, however, both structural and philosophical semantics have in their own different ways "expelled" the conceptual dimension.

83. From a developmental point of view, one could hypothesize that linguistic communication is a more perfected and evolved form of ostensive-inferential communication, unique to the human species.

84. By this I am in no way claiming that lexical meanings can vary indefinitely according to each context of use (or experience). On the contrary, linguistic meanings relate to the structured and regular dimension of our experiences, according to an idea very similar to that of habit in Pierce. This issue will be developed in chapter 8.

85. A similar position is also adopted by Wierzbicka (1972), which I will return to later.

86. For an analysis of verbs ol movement, see also Violi 1996b.

87. Another area is expressions concerning spatiality. See Violi 1991.

Notes to Pages 48-60

88. See in particular the work of Marconi (1997). There will be further discussion of this point in 7.5.4.

A Synthesis and Some Problems

1. Cf. Eco 1984, Manetti 1993.

2. "66. Consider for example the ptoceedings that we call 'games'. I mean board games, card-games, Olympic-games, and so on. What is common to them all?—Don't say: 'There must be something common, or they would not be called "games'"—but look mid see whether there is anything common to all.—For if you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that. To repeat: don't think, but look!—Look for example at board games, with (heir multifarious relationships. Now pass to card-games; here you find many correspondences with the first group, but many common features drop out, and others appear. When we pass next to ball-games, much that is common is retained, but much is lost. Are they all 'amusing'? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition between players? Think of patience. In ball games there is winning anil losing; but when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared. Look at the parts played by skill and luck, and at the difference between skill in chess and skill in tennis. Think now of games like ring-a-ring-a-roses; here is the element of amusement, but how many other characteristic features have disappeared! And we can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way, can see how similarities crop up and disappear.

"And the resulr of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities of detail.

"67. I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than 'family resemblances', for the various resemblances between members of a family: build, features, color of eyes, gait, temperament, etc. etc. overlap and criss-cross in the same way.—A nd 1 shall say: 'games' form a family" (Wittgenstein 1953: 46).

Regularity and variation in language

The set of semantic competences that I have outlined and discussed thus far can be defined as a controlled idealization, or at least a controllable one, in the sense that there are standards on which to base verification criteria and procedures for evaluating the extension and value of such competences. Dictionaries are specific registers that bear witness to the possibility of intersubjective control; the updating of dictionaries, which verify collective agreement on linguistic change, demonstrates the possibility of a continual process of diachronic adjustment between inventories and usage.

The meaning attributed to the words of a language by individual speakers is thus regulated by a general, intersubjectively founded convention which, within a given linguistic community, is assumed to have a regularity that underlies use and the inevitable variations in individual competence. Competence, convention, and linguistic community are mutually related terms; the meaning for which competence is presumed is that which is assumed to be shared within a given community. This presupposes the existence of a regularity of linguistic meanings: we have competence in the standard, regular meaning of a term, which is conventionally delimited by the language.

For lexical semantics, regularity, or typicality, may be the most important idea to emerge from the study of categorization processes. In chapter 5 I suggested a distinction between protypicality and typicality, in order to indicate two cognitive modalities for organizing sense that are connected but different, a difference that has not always been adequately underlined. Prototypicality relates to the existence of a more significant exemplar of a category, such as the sparrow or swallow in the category of birds. As I have already pointed out, this meaning is only oresent at the basic level of the categorial hierarchy; when we shift to the subor

dinate or superordinate levels, the sense of "prototype" changes and is no longer "a type of" but the standard case, the average exemplar. If the prototype of bird is a sparrow, the prototype of sparrow is the typical sparrow, the most regular case. This second meaning of prototypicality, which I proposed calling typicality, is more important for lexical semantics, in that the idea of "average value" as typical value can provide a basis for the representation of lexical meaning. The first meaning, though fundamental in categorization processes, is less pertinent for semantics because, as we have already seen, the most characteristic exemplar certainly does not represent the meaning of the category (sparrow is not the meaning of bird). Semantic theory's interest in psychological studies of categorization lies principally in their empirical verification of the psychological reality of the concept of regularity.

The idea of an underlying regularity is also present in the concept of the encyclopedia formulated by Eco, as can clearly be seen in his discussion of the concept of background and the assumptions of background proposed by Searle (1978). According to Searle, the dependence of meaning on contexts is not entirely predictable and consequently literal meaning must always be measured by a set of background assumptions that are never entirely definable and determinable, in that the specification of one throws into doubt the definition of the others, setting up a process of infinite regression. Eco (1984) contests this process of infinite regression and argues that there are intertextual frames or stereotypical situations establishing what we can define as the canonical form of certain contexts.

This canonical form is what I call regularity of meanings, and only in relation to this regularity can one define variation and thus also understand limit situations like those described by Searle. Indeed, the paradoxical nature of the examples suggested by Searle, and the immediate recognition of this (the two-meter hamburger, the hamburger placed in a block of Plexiglas, etc.) sound like an indirect confirmation of the concept of the regularity that it seeks to deny. It is no accident, in fact, that in order to sustain the indefiniteness of meaning, Searle tesorts to the construction of deviant examples, as Cosenza (1992: 121) has observed. In reality, normality and variation from the norm are concepts that refer to and define each other, and it would not be possible to classify a context or meaning as deviant if there were not a canonical form from which it varied.

One must not think, therefore, that regularity excludes variation, but see these terms as the extremes of a dialectic polarity inscribed in the nature of language itself. There is a constant tension in language between stability and instability, between regularity and innovation: language is neither a completely stable system of representation nor an agglomeration of continual variations without structure. Meanings are transformed not only diachronically but also synchronics ally, in that a certain degree of plasticity inheres in language, permitting ongoing adaptation to contextual variations; at the same time, there is an element of stability to meaning which permits us to mean and to communicate. Language is sufficiently flexible to allow us, in an appropriate context, to describe a pile ol books as a chair, but ai the same time it is sufficiently constituted to ensure the

stability of the typical meaning of chair; the innovative and creative possibilities of language do not imply the absence of a stable dimension in language. On the contrary, they presuppose it.

I will now deal with the regularity with which linguistic forms are associated to typical situations, because the forms of this regularity, and their possible representations, constitute the subject matter of linguistic semantics. The role played by the stable, conventional, even repetitive aspect of linguistic functioning provides a new approach ro one of the crucial problems for every discussion of meaning, that is, the problem of context.

Two views of context

Practically every discussion about the role of context in the determination of meaning starts with the vexata quaestio of its extension: what exactly should context include? How can we fix its limits? There is no agreement at all on what we should take as being context; the notion ranges from the entire encyclopedia understood as the historical and cultural horizon within which each text is collocated, to the extralinguisric "surroundings" that constitute the communicative situation of a given utterance, Го the strictly restricted linguistic context, which is sometimes termed co-text. This range reflects the perspectives of the disciplines which have cause to resort to context: the restrictive reading of context as Unguis tic surround or co-text is characteristic of textual grammatical studies,1 while anthropology, ethnology, and sociolinguistics tend to extend the area of application to the more general socio-cultural aspects underlying communication.2

The different notions of context reflect different methodological perspectives which, as Bertuccelli Papi (1993: 186) has observed, depend both on the objectives of the analysis and on the object of study. From the point of view of the determination of lexical meanings, the question of how far context extends can he posed in a way that is in some way at odds and partially independent of its definition: the real problem is how to view the relation between lexical meaning and contextual components, both intra- and extratextual. This relation is often seen as a series of transformations effected by context on a hypothetical pre-existent and non-contextual meaning. Posed in this way, the problem presupposes an implicit opposition between meaning in context and meaning outside of context; however, we shall see that talk of non-contextual meaning is misleading because meanings "outside of context" do not exist in reality.

The equivocation derives from the widespread and unquestioned acceptance of what I would define as an externalist view of context—how much and in what way a certain "surround" modifies the meaning of a word. I would like to attempt to shift the perspective, to turn it inside out and give it an internal focus. We can ask not so much what (he context does to the word but above all what the word does to the context, what sense-producing potential the word has in relation to its "surround." I will call this an internalist perspective.

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2016-08-11

lectmania.ru. Все права принадлежат авторам данных материалов. В случае нарушения авторского права напишите нам сюда...