Категории:

ДомЗдоровьеЗоологияИнформатикаИскусствоИскусствоКомпьютерыКулинарияМаркетингМатематикаМедицинаМенеджментОбразованиеПедагогикаПитомцыПрограммированиеПроизводствоПромышленностьПсихологияРазноеРелигияСоциологияСпортСтатистикаТранспортФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияХоббиЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

The schematic nature of meaning

The idea of a context of regularity refers to the schematic nature of meaning, where schematic nature means that single terms can be seen as synthetic, condensed forms of underlying schemes with complex content. The schematic nature of meaning can be effectively represented through the family of concepts that go by the name of frame, schema, scene, scenario, intertextual frame, and the like. I

will not traie a complete history of these concepts, which would take us all the way hack to Kant's idea ol the schema as an organizing element of experience, nor examine all the meanings that have been attributed to these terms by various writers. Though important, such distinctions do not directly concern the problem that we are discussing here.6 It is sufficient to bear in mind that the elaboration of schema or frame concepts is always directly connected to a theory of knowledge— indeed, it is essentially a theory of knowledge.7 The basic hypothesis is that knowledge is structured on the basis of organized sets of concepts that are systematically linked to each other in schemata or frames. Understood in this way, these notions can prove extremely useful for semantic representation and in general for a theory of lexical meaning.

Fillmore (1975) was the first to apply these concepts to lexical semantics, which led to the development of a more systematic model, frame semantics, and in the next decade, to ever more frequent studies and research in this direction.8 Fillmore's model provides an interesting example of a schematic representation of lexical meaning based on the same idea of regularity that I have developed thus far. There is a continuity between the notion of frame and Fillmore's early work on case grammar (Fillmore 1968), which in turn was inspired by the concept of valency developed by Tesniere (1959). In case grammar, the grammatical position of individual predicates, often marked in language by inflection, was connected to a schematic representation of the deep cases compatible with them.9 The notion of "case roles" for a verb contains the kernel of the idea that would be developed in frame semantics: the frame is the development of the schematic representation of the roles connected to a predicate, with the addition of a richer background of encyclopedic knowledge, as well as the possibility of extending the schema to other parts of the discourse.10

The basic hypothesis is that:

Particular words or speech formulas, or particular grammatical choices, are associated in memory wirh particular frames, in such a way that exposure to the linguistic form in an appropriate context activates in the perceiver's mind the particular frame—activation of the frame, by turn, enhancing access ro the other linguistic material that is associated with the same ftame. (Fillmore 1976a: 25)

Fillmore also proposes a distinction between different levels of analysis; in particular, it is important to keep the lexical linguistic level (which I will from now on term the frame) separate from the underlying conceptual scene, which refers to our experience of the world, an experience that is highly structured and organized according to a describable and predictable regularity:11 the scene includes experiences, actions, objects, perceptions of the world, and the memory of them. The possibility of understanding and using language lies in and is relative to our knowing the underlying scenes, or in other words, to our possession of a shared (and shareable) experience of the world.

The fundamental aim of semantic theory is to describe the relations between the various terms that constitute a particular linguistic frame, projecting it on the

background of the scene which they refer to, a scene that could be described in another language by means of a different linguistic grid. For each term, the following must be specified: the scene or group of scenes activated by the term, how the term in question combines with the other lexical elements that relate to the same scene, and what grammatical relations the terms have with each other. For example, the meaning of write (Fillmore 1976b) requires specification of the underlying scene relating to the activity in which someone leaves particular signs on a surface with a pointed instrument able to leave such a trace. Write also necessarily implies that the signs produced are linguistic, which permits us to distinguish the scene of write from that of draw or paint, activities which produce iconic signs, in turn differentiated according to the type of instrument used (pencil or brush). This specific grouping of scenes is culturally defined: Japanese, for example, does not have different terms for writing, drawing, and painting. The verb kaku denotes the production both of words and phrases and of sketches and paintings, given the particular importance attributed in Japanese culture to the calligraphic, pictorial component of writing. The different organizations of the English and Japanese lexicons can only be represented by reference to the different overall scenes that the words relate to, thus integrating the relativism of cultural structure into semantic representation.

In European languages, the scenes linked to the activity of writing are highly differentiated and specific: consider that besides write we possess verbs like copy and sign which select very restricted forms of writing, either in relation to the product and the way it is produced (sign applies only to our name written in such a way as to constitute a signature) or in relation to the nature of the text produced (in the case of copy, its non-originality). In the model proposed by Fillmore, this information is specified in the linguistic frame, primarily through the structure of associated cases.12 Write, for example, implies an agent that carries out the action and which appears in subject position, an object produced by the act and a surface on which to perform the action, which can occupy the role of direct object with various verbs {to write a letter, to paint a chair), and finally the instrument used (normally introduced in English by the preposition with).13

A schematic representation of this kind presents a number of significant features that belong to every experientially and abductively oriented form of semantics. In the first place, there is a definite choice of an encyclopedic and not a dictionary representation. Scenes, the central nucleus of the representation, can be seen as codified and stereotypical segments of a given culture and consequently of the knowledge and experience of the world of the speakers of that culture; knowledge of the world is a necessary part of the linguistic description.14 In the second place, the representation is conceptual more than it is lexical: if it manages to give an account of the structure of the lexicon of a given language, it is only in so far as it represents the underlying conceptual structure. This kind of semantics is not only a theory of how a language is built, but above all a description of the way the concepts and knowledge expressed by that language are organized. We might say il is an ethnography of the culture and knowledge underlying the language.

Regularity and Context

In the semantic model that I am trying to delineate, the concept of the scene (and the correspondingly connected linguistic frame) represents three fundamental dimensions of meaning, dimensions which are interconnected yet which also possess a relative degree of autonomy:

1. The dimension of regularity of meaning, in particular the regularity of contexts which is the basis of the schematic nature of meaning. We could consider this aspect the positive component of meaning.

2. The contrastive component of meaning, which depends on the relations between terms. The lexicon is not a simple list, but a structured set in which the value of each term depends on the value of the others according to a "negative" system of differences which requires a non-atomistic treatment.

3. The narrative component of meaning, made visible in the moment when single lexemes are conceived of as condensations, or surface manifestations, of deeper and more articulated conceptual and narrative schemata.

Let's look more closely at these three aspects.

8.}.i. The positive component: Scenes and prototypes

The concept of scene proposed by Fillmore has notable conceptual affinities with the second meaning that I proposed for prototype, namely the typical token of a certain entity, event, or situation. Just as the prototype of chair refers to the typical and most common chair, so the scene can be seen as the typical context of a given action: the scene activated by write represents the standard context of application of the term, its typical case, in which a human subject traces onto a surface (typically a sheet of paper) words and sentences, making use of a specific object like a pen or a pencil for this action. Clearly, it is also possible to write with a pin on the vertical surface of a wall, but expression of this requires, like all non-typical tokens, additional specifications. Generally, what holds for the prototype holds for the scene: in the absence of further information, the term activates its typical context of use or, if one prefers, the typical context constitutes the background that allows understanding of the meaning and regulation of its use. In the cases of both the prototype applied to entities and the scene applied to complex actions or events, it is possible to distinguish between essential and typical components, even though this distinction is not always explicitly rendered in the models developed thus far (for example, Fillmore's frame semantics almost always limits itself to representing essential properties).

The difference between scene and frame on the one hand, and prototype on the other is essentially terminological and largely derives from the different kinds of entity that have been referred to by these terms in the various disciplines that have used them. The literature on prototypes refers primarily to concrete objects- natural kinds and artifacts—because these entities are best suited to con

trolled experiments on categorization processes. At the level of linguistic application, this led, at least initially, to a semantics that was almost exclusively nominal. Subsequent models, in particular Fillmore's frame semantics, dealt prevalently with the representation of verbs and corresponding complex actions, following a tradition that stems from the idea of the valency of predicates. This field of investigation explains why scene 2xA frame, rather than prototype, are the terms adopted, given that the representation of verbs does not so much require typical properties as a characteristic action schema for a given sequence. The opposition, however, is more of point of view than of substance; just as we can say that the typical chair is the one characterized by a certain set of properties, so too the typical action of writing is the schema of certain roles and the sequence of actions that we normally associate with this term, and which the concept of scene attempts to capture. The affinities become more evident if, instead of concrete object terms, we consider terms like orphan, mother, divorce, restaurant, and so on, whose semantic representation involves reference to a complex scene, as we shall see in section 8.3.3. What the prototype and the scene have in common is the same intuition about the nature of meaning, to be precise, the one that I have proposed to call regularity of context: each term activates and refers to its own standard context of reference, whether that is the token of a typical referential entity (in the case of concrete objects) or a typical situation, understood as a dynamic action schema.

Fillmore's slogan (1976b: 84) "meanings are relativized to scenes" is equivalent to the affirmation, in the terms that I have proposed, that each word is always indexed to a standard context of reference, which constitutes the indispensable background for interpretation and use. The link between lexical meaning and scenario (or standard context) is twofold and presupposes two readings: the context or typical scene is the ground on which the conventionality of lexical meaning rests (in the direction context —» word) and, conversely, each term activates the relative scene or context of reference (word —> context).

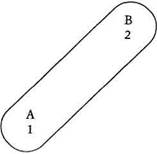

Fillmore proposes the example of the commercial sales event. The prototypical cognitive scene consists of a person who comes into possession of some form of goods from another person through an agreement which involves a transfer of money from the first person to the second. The scene thus includes four entities: buyer, seller, goods, and money, as can be seen in diagram 15. This scene represents the deep conceptual level presupposed in the understanding of the single terms that form part of the same linguistic frame (such as buy, sell, pay, spend, cost, etc.), and that are projected on it. Observe, for example, the frame of buy indicated in diagram 16: the ringed element indicates the part of the scene put into focus by the verb, numbers 1 and 2 indicate the grammatical relations of subject and object, and the external elements are the optional complements that can be expressed through the prepositions indicated.

The distinction between the deep conceptual level of the scene and the linguistic one of the frame can also productively account for particular semantic

------------------------------- commercial exchange ------------------------------

В

(goods)

А С

(Buyer) (Seller)

D

(money)

Diagram 16

phenomena such as relations of synonymy and semantic opposition. Fillmore develops this point by examining the relations between terms belonging to the same scene, for example, the converse terms sell and buy, which display a superimposi-tion of meaning. I would like to suggest that the analysis can also be extended to terms that do not belong to the same scene. Let's take as an example the case of get. Unlike buy, its representation does not involve any concept of exchange, just the transfer of something. Get can be represented by the schema in diagram 17, which has just three roles. In English, however, the two verbs are fully interchangeable in certain contexts:

8a. Did you get the newspaper today? 8b. Did you buy the newspaper today?

9a. I forgot to get the bread. 9b. I forgot to buy the bread.

In order to explain the systematic nature of these substitutions it is not enough to say that the context determines the selection of certain features; in fact, it is the regularity of the selection process that is interesting in these cases. What ensures that in these contexts get is systematically interpreted as a synonym of buy? It seems to me that the regularity of the substitution can easily be explained by referring to the underlying schematic structure: get is interpreted here against the background of the scene of the commercial sales event that underlies buy and thus activates that part of the frame present in buy but not in get, that is, the component of "exchange" instead of the pure "transfer." The activation of this frame modifies the meaning of get and allows a synonymous substitution.

The articulation of a deep conceptual level displays the experiential (and in this sense also realistic) characteristic of semantic representations of this kind: words are understood only if they are projected on the complex background of our experience of the world, which means that the semantics of language is inseparable from a "semantics" of the world and our experience of it. This reveals the intrinsically encyclopedic nature of the model, which involves much more than the quantity of information included. From a purely quantitative point of view, the schema of the commercial exchange proposed by Fillmore may appear rather "flimsy," because it includes only those roles essential to the definition of the concept, leaving out, for example, typical elements that are more closely connected to the cultural connotations. The encyclopedic nature of the model can also be seen in its format, which is semiotically "mixed" and not reducible just to linguistic properties; the frequent and characteristic use of figures, diagrams, and iconic representations within frame semantics and many other models developed in the field of cognitivism is significant from this point of view.

I----------------;---------------------------------- set --------------------------------------------------1

с

(source)

I )iagnun 17

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2016-08-11

lectmania.ru. Все права принадлежат авторам данных материалов. В случае нарушения авторского права напишите нам сюда...